Bamboo blooms simultaneously in a number of forests in northeastern India every 48 or 50 … [+]

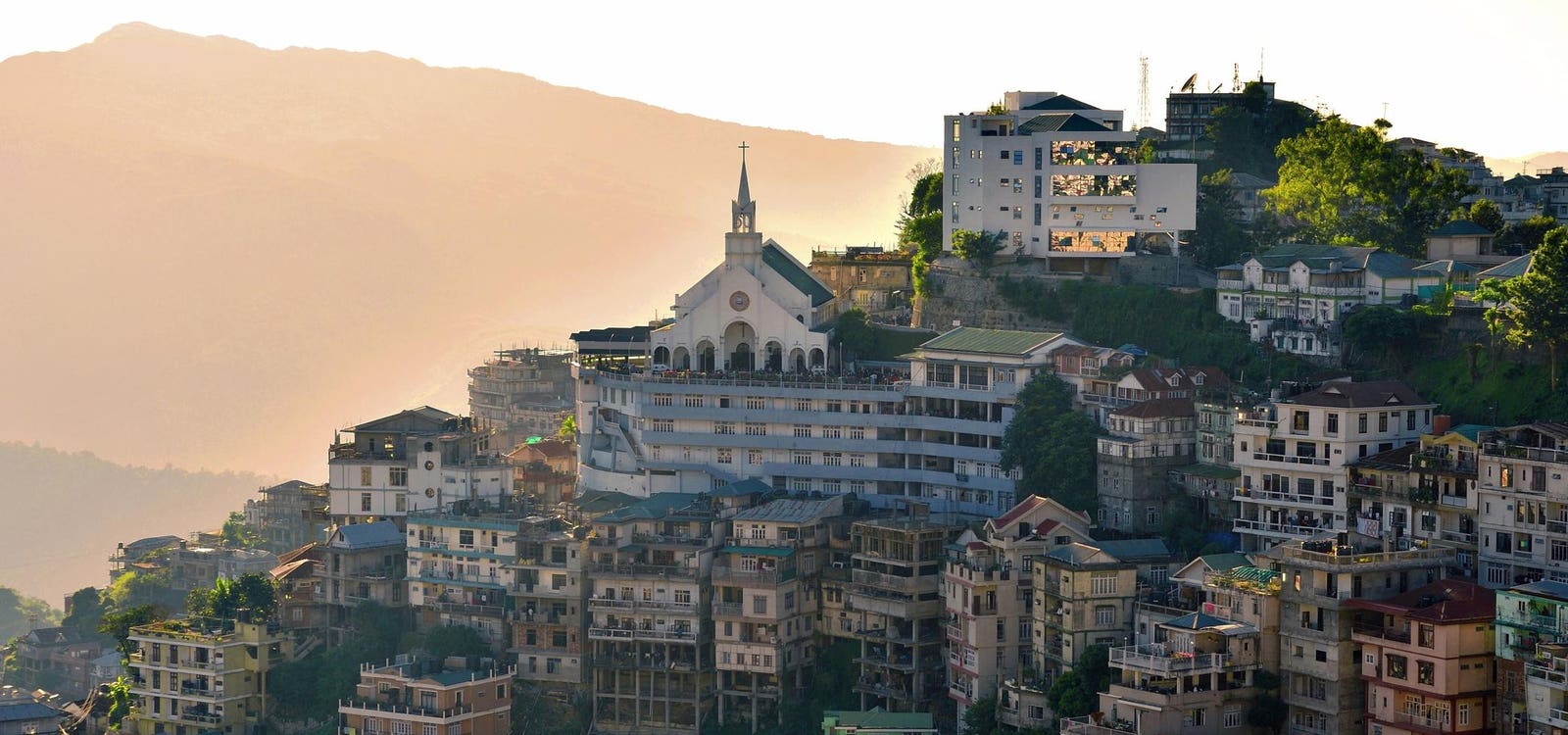

India’s northeastern state of Mizoram and some of its neighbors were devastated by a famine in 1911. Forty-eight years later, the same thing happened again in 1959. When it happened again in 2007, it could no longer be done. chalk coincidence.

The Mizoram government has recorded famines occurring roughly 50 years apart in the state for more than two centuries, starting in 1815. The locals even have a word for this cyclical phenomenon – “mautam”, and it all starts with flowering of young bamboo.

Although most people imagine bamboo as a monstrous, tree-like growth, it is actually a grass, albeit a massive one. Its life cycle is remarkable and almost mystical.

According to an April 2020 study published in the journal, Frontiers in Plant Science, flowering cycles of bamboo species can range from 3 to 150 years. During the flowering stage, all plants of the same species bloom together, resulting in a spectacular explosion of bamboo flowers.

But, as you will understand, this synchronicity is largely responsible for the recurring famine in northeast India.

And this is not an isolated and unique phenomenon only for these parts. From Hong Kong to South America, the blooming of a few bamboo flowers heralds an overwhelming “rat flood” to follow, followed by crop destruction, economic turmoil and famine.

As a bloom it presents an explosive problem in Northeast India

The mass flowering of bamboo is spectacular but rare, with cycles lasting anywhere from 40 to 120 years. For example, in Mizoram, Melocana bacciferaa widespread species of bamboo known locally as “mautuk” (after which the phenomenon of mautam is named) blooms once every 48 to 50 years. When it does, millions of bamboo plants produce large amounts of seeds at the same time.

When bamboo forests bloom at once, the abundance of seeds invites a virtually endless crowd. … [+]

These nutrient-rich seeds become an irresistible feast for the region’s black rat population (Rattus rattus), which spreads rapidly under such favorable conditions.

Fed by the abundant supply of seeds, the number of rats increases to extraordinary levels. But as the seeds are eventually consumed, the mice’s desperation for food drives them beyond the forests and into human settlements. Fields of rice, corn, and other staple crops are soon ravaged by waves of hungry rodents, leading to widespread crop destruction. This invasion escalates into a full-blown agricultural crisis, bringing famine to the affected regions.

As if that wasn’t bad enough, Mizoram also has something called a “thingtam”, which is the same idea as a mautam, except this time, there’s a different species of bamboo to blame –Bambusa tulda. This species has its own distinct flowering cycle, occurring approximately every 30 years.

In other regions with bamboo species such as Arundinaria alpine in Ethiopia and Bambusa tulda in Japan, similar cycles of flowering, fruiting and dying have been recorded, all accompanied by waves of rat infestations and subsequent ecological imbalances.

This isn’t your average rat infestation – it’s a flood of rats

With an abundance of bamboo seeds to eat, rats descend in droves. In one case – recorded in a study published in Rodent Outbreaks: Ecology and Impacts— Rat infestation consumed over 30% of bamboo seeds in Chittagong, Bangladesh.

During these “masting” events, rat populations can grow exponentially, as the available food supply accelerates breeding rates and reduces natural controls such as cannibalism. Populations of species such as Rattus rattus it can fly up, creating what the locals call a “rat flood”.

Mice grow and multiply very quickly, especially when there are many nutritious seeds … [+]

But the impact doesn’t end in the forests. Once the bamboo seeds are depleted, the rats – now numbering in the millions – begin to migrate towards human settlements in search of new food sources. They invade cultivated fields and barns, devouring everything in their path.

The ripple effects extend beyond simple crop loss. As the rodent population explodes, so does the risk of rodent-borne diseases. In some cases, the infestation leads to outbreaks of diseases such as bubonic plague and hantavirus, which can be transmitted from rats to humans.

The cycle of bamboo flowering, rat infestation and crop destruction disrupts the entire ecosystem, leaving farmers and villagers to face not only food shortages, but also increased health risks and financial ruin.

The human cost of a bamboo flower

Historical records and local proverbs attest to the deadly consequences of rare bamboo flowering. The Mizo people of northeastern India, who have endured this phenomenon for generations, have a saying: “When the bamboo flowers, death and destruction will follow.”

From northeast India to Bangladesh and beyond, bamboo blossoms are almost always followed by plagues or famines that severely affect the local population. In fact, the boom in Mizoram in 1959 even resulted in a local uprising.

Other regions across Asia and beyond have experienced similar disasters. In Hong Kong, where Bambusa flexuosa AND Bambusa chunii blooms every 50 years, flowering events in the late 1800s coincided with an increase in bubonic plague cases. Observers noticed a parallel increase in the rat population, suggesting that the bamboo bloom indirectly contributed to the spread of the disease.

While efforts have been made to mitigate the damage, including tracking bamboo flowering cycles and improving rat control measures, the phenomenon remains a powerful and unpredictable force. For rural communities, especially those in bamboo-rich regions, the memory of these breadcrumbs remains vivid—a reminder of the dangers behind what appears to be a simple plant life cycle.

While the bamboo boom is a miracle of evolutionary synchronization, its consequences reveal a complex web of interdependence and disruption, much like Australia’s reed overpopulation. The seeds that feed rodent populations eventually become the seeds of destruction for human communities, turning bamboo forests from natural resources into sources of danger.

As scientists continue to study these cycles, understanding the dynamics of bamboo flowering and rodent population growth can help improve preparedness for future events. Meanwhile, the people of northeast India and other affected areas live with the knowledge that one day, the bamboo will flourish again.

Events like bamboo flowering show us the true scale of nature’s operations and where we fit in. How do you feel about the delicate relationship we share with nature? Find out where you stand Relation to the scale of nature